It's no secret that I like to use my Unistellar telescopes to track down obscure things and to create animations of them moving in the sky. Back in August I managed to track down Saturn's faint moon Phoebe (on my blog here).

Now that Jupiter is in opposition its time once again for me to take a look at it and some of its family of moons. The four Galilean moons are bright and easy to see with any optical magnification - even binoculars will work if you can hold them steady enough.

Here's a shot of them taken in late October when Jupiter was also near enough to a background star that was almost as bright as one of the moons.

The animated gif below is from two images taken 58 minutes apart on 9 November 2023. Himalia can be seen moving pretty close to dead center and the glow of Jupiter is on the left. I circled it to make it easier to see.

That worked out pretty well. Well enough that I wondered if there were any other Jovian moons that I might be able to catch.

Moons like Amalthea are bright enough, but far too close to the glare of Jupiter for me to ever be able to see. Some of them are just too small and faint, but Elara is just bright enough and far enough from Jupiter for me to be able to photograph it with my 4.5" telescope.

Elara and Himalia are in the same group (the Himalia group) of Jovian irregular satellites. With a diameter of 105.6 miles Himalia is larger than tiny Elara, which is just 53 miles across. As you can see from the graphic above (which I created using the SkySafari app), Elara is a bit farther away from Jupiter. It takes 260 days (8 1/2 months!) for it to complete an orbit around Jupiter. Himalia orbits just a bit faster, swinging around Jupiter ever 251 days (That's still a long time.).

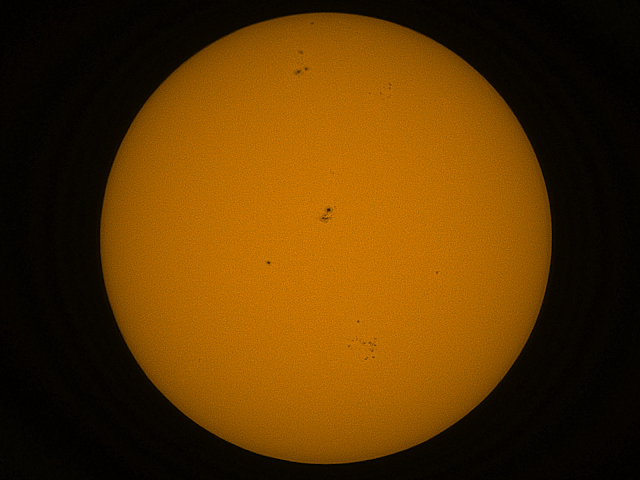

I was a little worried because I had some cirrus clouds in the way and SkySafari (by far my favorite astronomy app) doesn't always have the best coordinates for these faint irregular moons. I pointed my telescope at the position listed and saw this:

There's a moving object in the lower right corner which at first I thought was Jupiter's satellite Elara. It was only later (after I put up an earlier version of this post) that I realized that I hadn't checked to see if there were any known asteroids in the area. Sure enough, that's the asteroid known as (933) Moultona.

Well, rats. What I needed was more accurate coordinates. Thankfully, JPL's Horizons System is an easy resource for getting accurate coordinates for small solar system objects.

I pointed my 4.5" telescope at the right place and gave it another shot. Was I able to spot a moon that's just 53 miles across from a distance of over 376 million miles? Yes, though the glare from Jupiter was far worse than it was for Himalia (and strangely red too).

It's pretty tough to spot in the full frame, so I have posted a cropped animated gif version with Elara in a circle.

Here it is:

Pasiphae has a retrograde orbit (meaning it orbits backward relative to the orbits of all of Jupiter's regular moons) that takes 764 days to complete. Yes, it takes just over two Earth years to circle Jupiter! Since Pasiphae and even Elara and Himalia take so very long to circle Jupiter, what we are seeing here isn't much of any of their orbital motions. Instead, most of their motion in the sky is because Earth itself is a moving object. During the hour or sow between images Earth moved much more in its orbit around the Sun than Jupiter and its family of moons did, allowing them to be seen against the much further background stars.